The Project

Deanery Digests are short, plain language summaries of the Department of Education’s research outputs. This Deanery Digest is based on the following two open-access reports:

- Lindorff, A., Stiff, J., & Kayton, H. (2023). PIRLS 2021: National Report for England. Department of Education. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/pirls-2021-reading-literacy-performance-in-england

- Lindorff, A. & Stiff, J. (2024). Additional findings from PIRLS 2021. Department of Education. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/pirls-2021-reading-literacy-performance-in-england

What is this research about and why is it important?

The Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) is an international comparative study of the reading performance of students around 10 years of age. This corresponds to what is considered the ‘fourth grade’ internationally, or year 5 in England. PIRLS focuses on three aspects of reading literacy; how students read different types of texts (broadly, fiction and non-fiction), what kinds of reading comprehension processes students use to understand those texts, and what attitudes students have towards reading. PIRLS allows for comparisons of performance between education systems (usually different countries) and also comparisons of performance over time, with each iteration of the study being conducted every five years. PIRLS results from previous cycles of the study have drawn substantial interest from educational policymakers.

Due to challenges raised by the global COVID-19 pandemic, data collection in some countries, including England, was delayed by a year and instead collected in 2022. In other countries, data collection was delayed by 6 months and tested slightly older students than would normally be expected. This has raised additional challenges in drawing comparisons between countries with differing periods of data collection.

What did we do?

- PIRLS is developed and organised internationally by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA), and was delivered in England by Pearson.

- A total of 57 education systems participated in PIRLS 2021, with England’s sample consisting of 4,150 pupils from 162 different primary schools. The team at the University of Oxford’s Department of Education produced the national report focusing on England’s performance in PIRLS 2021. We also produced an additional analysis report addressing topics of interest raised by teachers and other relevant practitioners.

- This digest provides a summary of our main findings. We look at how England performed relative to other education systems and in comparison to previous cycles of performance, how attitudes to reading have changed in England over time, and how performance in PIRLS relates to pupil characteristics such as gender, socioeconomic background, and prior attainment (e.g. in the year 1 phonics screening check or their teacher-assessed key stage 1 reading level).

What did we find?

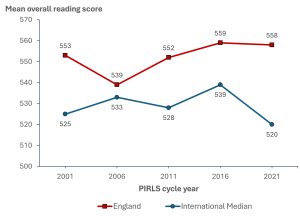

The graph below shows the overall reading scores in England (shown in red) and the median score of all participating systems in each cycle of the PIRLS study (shown in blue).

Figure 1: England’s PIRLS scores relative to the International Median across cycles

- The overall reading score of students in England did not change statistically significantly from performance in 2016, 2011, or 2001, but was statistically significantly higher than performance levels in 2006. Internationally, however, there was a large drop in the median of education systems’ average scores between 2016 and 2021, with most education systems experiencing a statistically significant drop in their average performance.

- In PIRLS 2021, students in England performed equally well when responding to fiction and non-fiction texts (known as Literary and Informational purposes of reading). This contrasts with previous cycles, in which students in England have consistently scored higher when responding to fiction texts.

- Pupils in England had higher performance on questions requiring higher-level interpretive and evaluative comprehension skills (known as Interpreting, Integrating and Evaluating) than they did on questions requiring more straightforward information retrieval and inferencing (Retrieving and Straightforward Inferencing). This was consistent with previous cycles of PIRLS in England.

- Girls in England, as well as in most education systems, scored statistically significantly higher than boys. However, the gender gap in England, which in 2011 was among the largest of all participating education systems, has narrowed substantially over time, with the gap now in line with the international average. Girls and boys in England scored similarly when responding to questions about non-fiction texts, while the gap in performance was wider when responding to fiction texts.

- The gap between the highest-performing (90th percentile and above) and lowest-performing (10th percentile and below) pupils in England narrowed slightly but not statistically significantly since 2016. Looking at the longer-term trend since the first PIRLS cycle, this gap between the highest- and lowest-performing pupils in England has narrowed over time, reflecting a slight decrease in the average score for the highest performing pupils but a substantial increase in the average score for the lowest-performing pupils.

- Pupils who were eligible for Free School Meals (FSM) scored 40 points lower than their peers who were not eligible for FSM, on average. Pupils eligible for FSM were also more likely to have lower confidence in reading, and were slightly more likely to report that they did not like reading, but did not differ substantially from their FSM-ineligible peers in their self-reported engagement in reading lessons.

- For children in year 1, as well as those in year 2 who had not yet met the expected standard in year 1, there was a significant, positive and moderate correlation between their phonics screening check scores and PIRLS 2021 scores in England. This does not prove the effectiveness of the teaching or testing of phonics as such, but it tells us that pupils who are fluent in decoding the sounds of written words and putting sounds together to read words aloud in early primary school are more likely to perform well in reading in later primary school, and vice versa. The gap between those who experienced early reading difficulties persisted over time, with nearly half of pupils who did not meet the expected standard in the year 1 phonics screening check going on to score at or below the “Low” benchmark and only about 20% going on to attain at least the “High” benchmark in PIRLS 2021. Early reading difficulties also appear to be related to being born later within year.

- In general, pupils who were more confident in reading tended to report greater liking of reading, pupils who reported more liking of reading tended to say they were more engaged in reading lessons, and pupils who were more confident in reading tended to say they were more engaged in reading lessons. However, pupils were equally likely to say they “somewhat liked reading” regardless of their confidence in reading, which suggests there is scope to encourage liking of reading even for pupils with less confidence. Further, about a third of pupils who reported being “less than engaged” in reading lessons also said they were “very confident” in reading, suggesting that some very confident readers might not feel sufficiently challenged in reading lessons.

What does it all mean anyway?

- The global COVID-19 pandemic impacted data collection for PIRLS 2021 and affected normal school operations in England and other education systems across the globe. We are not able to measure that impact directly, which complicates country comparisons and trends over time for this cycle of PIRLS.

- Some countries, including England, delayed data collection for 12 months and still assessed pupils around age 10. Other countries delayed by six months and tested pupils six months older than the usual PIRLS age. Still others continued with data collection as planned. This means that some direct statistical comparisons across these groups are not sensible to make, and rankings for this cycle should not be emphasised.

- Even with these complications, the benefits of PIRLS include providing systematic information on a representative sample of pupils in England, including:

- Measures of pupils’ reading performance for different types of texts as well as using different reading comprehension processes

- Information on pupils’ attitudes to reading; and

- Contextual information about pupils’ schools and teachers.

This information allows us to look at trends over time within and across countries, as well as making international comparisons. This is still true for the 2021 cycle of PIRLS, despite the fact that comparisons are somewhat more limited and must be interpreted with more caution than in previous cycles.

Open access reports

For those interested in further detail, the national report for England, as well as the further research report can be downloaded from the following pages: