The Project

This Deanery Digest is based on the following project: Pupil interactions and networks in special schools – Department of Education.

Digest prepared by Julia Badger.

What is this research about and why is it important?

This project aimed to better understand positive (friendship) and negative (bullying) interactions

between pupils who attend special schools in England.

Bullying is a public health risk, with international research from 40 countries showing that 37% of girls

and 42% of boys report bullying (World Health Organisation, 2020). This rate increases to 69% of all

pupils with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND; (Rose et al., 2011). Yet to date, there are

no evidence-based anti-bullying programmes specifically designed for use in special schools. This

could be, in part, because there is no data on positive (friendship) or negative (bullying) pupil networks (interactions) in either classroom settings or across the whole school for special school pupils.

A pupil network results from peer-nominations and can help us to see which pupils are friends, who plays or spends time with whom, and which pupils are involved in bullying either as the victim or perpetrator. This lack of network knowledge within special schools makes it difficult to design and structure a suitable and effective anti-bullying programme. Therefore, working with 156 pupils (aged 10-16 years) across three English special schools – each school with a differing specialism (School 1: Social, Emotional Mental Health, School 2: Cognition and Learning, School 3: Autism) – the research team collected positive and negative peer network data (as detailed below).

The findings from this project provide new insights into the positive and negative interactions and

networks between pupils in special schools. The findings will help to shape the development for a trial of the first fully adapted anti-bullying programme for pupils in special schools.

What did we do?

The team worked with as many pupils as possible from each school (see Table 1. Reasons for non-participation included parental withdrawal, repeated school absence, dysregulation or refusal to participate). To collect network data, the research team asked the following questions individually to each participating pupil:

“Think about all the children in your school:

- Who do you play with?

- Who are you friends with?

- Who is mean to you?

- Who are you mean to?”

For each question, pupils could nominate up to 10 peers in their school. The research team noted the names of those nominated. If a child nominated a pupil not participating in the study, that pupil’s name was not recorded.

Table 1. The number and proportion of pupils participating in each school.

| School | Primary specialism of the school | Number of pupils involved in the research | Percentage of the total school population (%)* |

| 1 | Social, Emotional and Mental Health (SEMH) | 39 | 63 |

| 2 | Cognition and Learning | 58 | 87 |

| 3 | Autism | 59 | 95 |

*Across the three schools, one pupil was opted out by their parents, twenty-three pupils did not want to take part, two pupils were too dysregulated, and nine pupils were absent.

The data were explored and visualisations of the networks and interactions between pupils were created (see below).

What did we find?

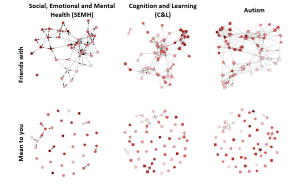

Below, you can see six network visualisations for the questions ‘Who are you friends with?’ and ‘Who is mean to you?’ (visualisations for the other two questions are not shown here). Each point represents a child: squares represent girls and circles represent boys. The shade of the point represents age: Palest = age 10 and darkest = age 16. The lines joining points represent a pupil connection; arrows indicate the direction of the connection, from the perspective of the child. For example, an arrow pointing from a pale circle to a dark square shows that a younger boy named an older girl in their answer.

Findings highlights:

- Number of nominations: All three schools had more nominations for positive ties (friends and play) than they did for negative ties (victimisation and perpetration)

- Friendship and play nominations: The Autism school recorded the most friendship nominations and play nominations on average followed by the C&L school and finally the SEMH school.

- Isolated children: The SEMH school was the only school to record friendship isolations: two children in this school neither named a friend nor were named as a friend by someone else. Three children in the SEMH school and three children in the Autism school neither named a playmate, nor were named as a playmate by someone else.

- Victimisation nominations: The Autism school had slightly more reports of victimisation on average compared to the C&L school or the SEMH school.

- Bully perpetration nominations: All schools had low levels of reported bully perpetration (bullies).

- Pupil hierarchy: Positive and negative relationships were relatively evenly distributed suggesting no dominant popularity or hierarchy in any of the schools.

- Role of sex and age: Although children formed positive and negative relationships with those of different ages and sex, they were far more likely to form same-age and same-sex relationships.

What does it all mean anyway?

This is the first study to collect social network data in UK special schools. This data can provide useful insight into positive and negative interactions in this vulnerable population which can inform the development of effective anti-bullying programmes.

Peer networks in these special schools were similar to those in mainstream schools in the following ways:

- The number and style of nominations

- More positive ties than negative ties

- More accusatory negative ties (Who is mean to you?) than confessional negative ties (Who are you mean to?)

- Positive and negative ties were more likely among same-sex and same-age peers

Peer networks in these special schools were different to those in mainstream schools in the following ways:

- More egalitarian when it comes to friendships and bullying: no dominant popularity or hierarchy of pupils in any of the schools

It is important to note that there were differences between the schools which suggests that we cannot, and should not, consider all special schools to be ‘the same’. Children and young people in each school have differing primary needs which need to be taken into account.

Although adjustments would need to be made for learning styles and levels, these data suggests that whole-school anti-bullying programmes – known to be successful in mainstream schools – could be trialled in UK special schools. KiVa-SEND, a whole-school anti-bullying programme adapted from the mainstream KiVa anti-bullying programme, is currently being trialled in eight UK special schools (Badger et al., 2025).

Material, data, open access article: N/A

This Deanery Digest has a CC BY-NC-SA license.