Blogs

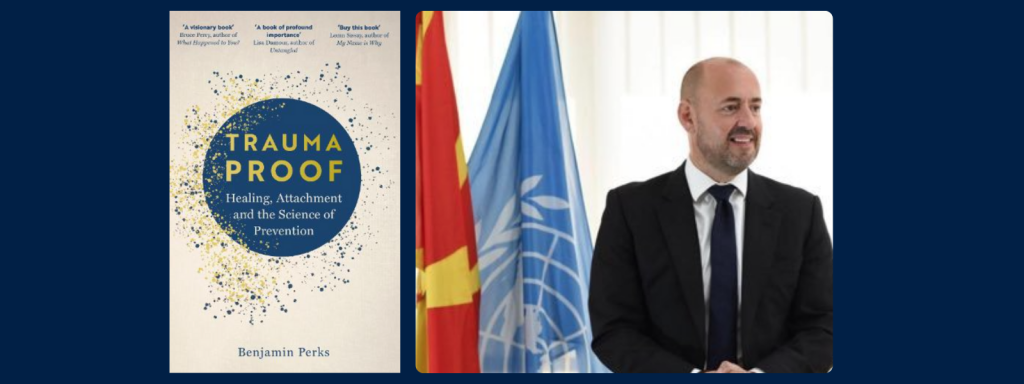

Ending child maltreatment: reflections on a Rees Centre webinar from Ben Perks

July 11, 2025

Oxford Cambridge Exchange fuels support network and collaborations among students

June 5, 2025

‘Raised by Relatives: The Experiences of Black and Asian Kinship Carers’ Action Planning Workshop

April 28, 2025

Dr Marta Garcia Molsosa’s Webinar: A Review of the Extant Literature on Factors, Interventions, and Educational Outcomes of Children in Care

March 28, 2025

Rees Centre welcomed Dr Calum Webb, Webinar Lunchtime Series: Does investing in prevention reduce rates of entering care?

March 13, 2025