Care leavers in Higher Education: new statistics but a mixed picture

Dr Neil Harrison, Deputy Director of the Rees Centre

The team in the Department for Education (DfE) that produces statistics on progression to higher education have really upped their game recently. Starting with a trial last December, they are now publishing an annual digest of statistics looking at a wide range of demographic and educational groups, helpfully including a backwards time series. The latest of these digests was published a couple of weeks ago and covers the 2018/19 academic year. Importantly, these statistics are based on linking – at the individual level – the data collected by universities with that collected by schools and colleges, providing a rich lens to understand inequalities in the system.

Interestingly, one of the groups explored is care leavers. I have written before about issues with the statistics produced from the data collected by local authorities (the so-called ‘SSDA903’ data) and the new DfE digest represents a significant step change as it reflects definitive records about who has gone on to higher education, including in further education colleges and private providers.

It’s also important to note that the definition of ‘care leaver’ used is slightly quirky, in that it is not the statutory one. The definition used for analysis is those children in care continuously for the 12 months up to 31st March in the academic year when they turned 16 (i.e. Year 11 for the vast majority). In other words, the definition captures only those with a good degree of stability, although they may have changed placements in this time. It effectively excludes most of those entering care at 14 or 15.

What do the new statistics say?

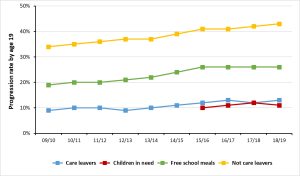

The statistics in the digest reflect progression to higher education by the age of 19 – i.e. allowing for one ‘gap’ year after school/college. There are issues with this that I will return to shortly. The data focused on English young people, but includes (most) higher education elsewhere in the UK. For the purposes of this blog post, I’ve brought together several of the groups covered by the digest into the time series chart below:

We look first at the blue line representing care leavers. The progression rate for 2018/19 was 13%. This is more than double the oft-(mis)quoted 6% figure that comes from the SSDA903 dataset and I am confident this is much more a realistic reflection of the situation. There has been a pretty steady rise from 9% in 2009/10, with a couple of one year blips, which is also good news. This fits well with what universities say – I hear many reports of a year-on-year growth in care leavers and other care-experienced students.

However, the yellow line shows the situation for young people who are not care leavers and this starkly demonstrates a persistent inequality – the progression rate for this group was 43% in 2018/19. If anything, the gap between the blue and yellow lines has widened slightly over the ten years of the time series, from 25 percentage points in 2009/10 to 30 percentage points in 2018/19. This is worrying, as it suggests that care leavers have not been able to expand their ‘share’ of higher education at the same rate as other young people.

As I discussed in my 2017 ‘Moving On Up’ report, it is important to remember that there are strong explanatory factors at work and when you compare care leavers with similar demographic and educational profiles, much of this difference disappears. For example, care leavers are significantly more likely to have special educational needs which impact on their attainment and therefore on their ability to pursue higher education – at least in the short term. We will almost certainly never be in a position to eliminate the gap, but we should collectively be aiming for these lines to converge over time.

How do care leavers compare to other disadvantaged groups?

The green line represents young people who were eligible for free school meals when they were in Year 11. There are, once again, issues with this definition and what it means, but this is a useful broad proxy for children who grew up in economically disadvantaged households. The 2018/19 progression rate for this group was 26% and therefore double that of care leavers. Again there has been a widening of the gap across the time series, from 10 percentage points to 13 percentage points.

Finally, the red line – for which only four data points are available – represents children designated as being ‘in need’ on 31st March in the academic year when they turned 16. Interestingly, the higher education progression rate for this group is actually slightly lower than for the care leaver group – e.g. 11% in 2018/19.

This is consistent with other analysis, including the Rees Centre’s recent report (with the University of Bristol) looking at educational outcomes for children in need. More research is needed to understand this fully, but it suggests that long-term and stable care placements – often, if not always – support progression to higher education in comparison to other young people experiencing profound challenges within their birth family.

Why is looking at progression at age 19 an issue?

All quantitative analysis of social data is driven by definitional issues. These are rarely neutral or objective – you have to decide what groupings to use, how you determine the boundaries and so on. As discussed, the new DfE digests use a particular definition of a care leaver – if they used a different definition, the analysis would yield different results.

One decision is about time cut-offs. This is always tricky. The longer timeframe you look at, the less reliable the historic data become – if they exist at all. The DfE’s cut-off at the age of 19 is a longstanding one and makes sense for the general population who most commonly progress immediately after school/college or after a gap year.

However, as I’ve shown elsewhere, this does not hold for care-experienced students. The social and educational disruption they undergo as a result of their care journeys means that they are often not qualified or ready to pursue higher education at 18 or 19. In fact, most that do go to university, do so in their 20s or even later in life. We don’t yet know for sure, but it is likely that something like 25-30% of care-experienced people will undertake higher education at some point in their life.

This is still not high enough, but the DfE digest – useful as it is – can only ever be part of the story and the blue and yellow lines would be closer if a longer timeframe were used.

A final note…

It is always important to remember that progression into higher education is only one side of the coin and that there is good evidence that care leavers and other care-experienced students are at greater risk of leaving higher education early. It would be great to see some official figures from the DfE on this at some point, to help us to understand the scale of the problem.

Contact Neil: neil.harrison@education.ox.ac.uk