How well is self-identification working for care-experienced students entering higher education?

Dr Neil Harrison, Deputy Director

For some years now, prospective students applying through the UCAS system have been given the option of declaring whether or not they are care-experienced. Aside from helping statisticians, this self-identification information is passed confidentially to their university when they join to help them to target additional support such as bursaries, accommodation, academic help and mental health interventions.

There has been concern about how effective this system is. For example, we know informally that some care-experienced students are reluctant to tick the box as they are worried about stigma or that it will negatively impact on their university application. Some applicants may not realise that they were in care if they were young or if it meant living with relatives in a kinship care arrangement. Furthermore, not all students enter higher education through the UCAS system.

Anecdotally, there are also some people who tick the box when they are not care-experienced. These applicants may not understand the question – perhaps think it’s about caring for other people – or tick it by accident.

False positives and false negatives

There are thus two issues. The ‘false positives’ who say they are care-experienced when they are not; these create a bit of extra work (to do the checking) and are potentially a source of error in statistics. However, the ‘false negatives’ are more concerning. These are students who should be entitled to additional support from their university, but who are not getting it because their university doesn’t know they are care-experienced. It is obviously useful for policy and practice to know how many false positives and negatives there are.

The data that we’ve assembled for one of our projects has enabled us to shine a partial light on the self-identification data. It doesn’t completely answer the questions as there are significant gaps in the data we have – we will touch on these later. However, it does give us some useful clues for the first time which we thought it would be useful to share informally.

Exploring the data

We have anonymous data for England relating to the cohort of people born in the 1995/96 school year and who remained in England between 11 and 18 – about half a million in total. We have been able to link data over time to combine care histories from the age of 8 (when the national data begins) and higher education up to the age of 21. Therefore, we know (a) whether the student’s university believes them to be care-experienced based on self-identification, and (b) whether they had indeed been in care.

To complicate matters, the university can allocate the student to one of two care-experienced categories. The definitions for these are very unclear, but we believe they are broadly intended to represent care leavers (meeting the statutory definition) and other care-experienced students.

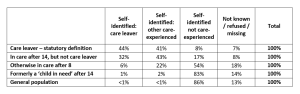

The table above summarises what we have found, based on the data that were held at the end of the student’s first year. There isn’t space here to cover everything, but some basic observations:

- It’s clear that universities are not collectively using the two care-experienced markers appropriately, with nearly half of care leavers are actually recorded in the ‘wrong’ category. The national data is therefore poor at differentiating between statutory care leavers and other care-experienced students.

- However, about 85% of statutory care leavers are being appropriately classified as care-experienced through self-identification. The other 15% are split between those stating that they are not care-experienced (i.e. false negatives) and for whom the data are missing (perhaps due to refusal).

- The system is also reasonably good at identifying other students who were in care after the age of 14, with 75% self-identifying, although 17% had stated that they were not care-experienced and 32% have been wrongly classified as statutory care leavers.

- However, students who were in care between the ages of 8 and 14 were much less likely to self-identify as care-experienced – only 28% did so, with over half explicitly saying that they were not care-experienced.

- The ‘children in need’ group are not care-experienced (having been allocated a social worker, but not entered care), but there was a small proportion (3%) who had self-identified as such (i.e. false positives).

- The same was true for the general population. The proportion was very small, but this represented over 500 individuals. Some of these are undoubtedly false positives, but others may have been in (and left) care before the age of 8, including those adopted from care.

Implications for policy and practice

This small piece of analysis is not intended to be the final word and it is limited in some important ways. For example, we only have higher education data up to 2016/17 and the situation has almost certainly improved somewhat since then, with markedly more attention on care-experienced students over the last five years. We also only have data on younger students aged between 18 and 21, so the situation may be different for those entering higher education at a later stage. However, there are some useful lessons from the data:

- Firstly, the way in which data is being recorded by universities varies widely and this is likely to be leading to confusion, both in the provision of support and in understanding who is entering higher education. I am aware that the Office for Students is currently seeking to address this with the Higher Education Statistics Agency, UCAS and universities, which is a very positive step.

- Secondly, there is clearly some degree of incorrect self-identification – this is likely to be mainly accidental and probably reflects misunderstanding about what constitutes ‘care’ in this context. Nevertheless, this does mean that the self-identification data cannot be taken at face value and does need to be subject to confirmation by universities, creating a small administrative burden to ensure that support is correctly directed at those entitled to it. This requires universities to have a good understanding of care and a mechanism to enable students to evidence their status as sensitively as possible.

- Thirdly, a sizable proportion of care-experienced students of various categories are being missed by the self-identification system, especially among those who left care prior to their teenage years. This suggests that there is much more work to be done to ensure that care-experienced students are aware of the benefits of self-identifying and feel able to do so without stigma. Clearly, however, they must always have the right to not share this information about themselves if they prefer – or to do so at a later date.

A positive development in recent years is that many universities have broadened out their support – extending out beyond statutory care leavers and removing age thresholds. This is to be welcomed as it is not just younger care leavers who experience educational disruption and who can benefit from additional help to enter, and thrive within, higher education. These data suggest, however, that there is still work to be done to reach all those who are entitled to receive it.